Chapter 11

The Barlows

We can now turn to the family which gives me my surname, the Barlows! My paternal great Grandfather, John Barlow belonged to a Cheshire family and was born on the 20th September 1815 at Chorley near Alderley in the old gabled and picturesque house known as The Oaks, a rambling place with polished floors and diamond paned windows, standing on the estate which had been in the possession of the family for about 200 years.1

He was the eldest of seven – three sons and four daughters – children2 to John Barlow (1789-1846) and Deborah Neild (1790-1850).3 By all accounts he was a very affectionate brother. He went away at the age of nine to the Friend’s school, Ackworth and was acknowledged to be “the cleverest boy in the class” as well as “the kindest and most amiable” according to a fellow pupil. John was from childhood of a rather sedate and grave demeanour and became interested in religious matters from an early age. His daughter, Mary writes in her diary:

“In 1824 at the age of nine, my Father went to Ackworth School in South Yorkshire, where he remained for four years. This was not the age of holidays in Friends’ school and when he returned home, so altered was he that his mother, who had not seen him since he first set off for school, did not recognise him!”4

John’s father was a Farmer and it was always assumed that when young John grew up, he too would remain at home and help his father in the running of the farm, which for some time he did. But he always had a strong love of animals, particularly of the farm cows and during the years on the farm he spent much time in the study of those diseases to which domestic animals are prone. And it was this which guided him into the choice of profession that later took him to Edinburgh. He also developed a fondness for poetry and was himself an original writer exhibiting a deep love of nature and of home and he was a much cherished eldest son in Chorley.

Eventually his own devotion to study was too strong and brought about a change in his life. By the time he was in his twenties, he decided to go to Edinburgh to study veterinary science and in 1842 he enrolled at William Dick’s Veterinary College in Clyde Street, Edinburgh. He gained his diploma there in 1844 and was awarded a prize for the scientific paper he wrote ‘On the Present Epidemic among Cattle’ and a silver medal “Awarded to Mr Barlow as the student most distinguished at the examination for diplomas.” That same year he was awarded another silver medal for his essay on ‘Puerperal fever in the Cow’.

An article that appeared in the North British Agriculturalist, refers to the work of the next few years:

“After attending two sessions at the College he obtained his diploma, having been the most distinguished student of the course. The following session he acted as demonstrator and in

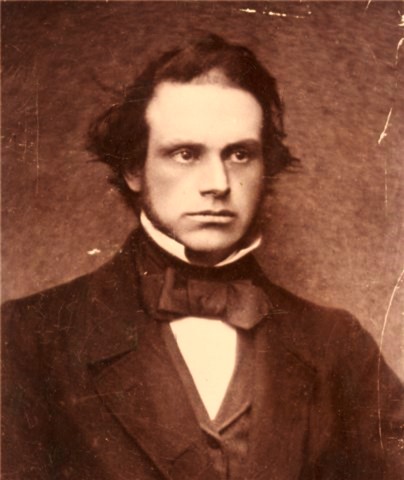

Professor John Barlow

1845 was appointed Assistant Professor and lecturer on zootomy,5 including the anatomy and physiology of domesticated animals.”

He later moved full time to Edinburgh and it is obvious that he found a conflict in the Christian way of life in which he had been brought up and that his parents wished him to follow. This often led him to eschew the more convivial side of university life, and he wrote to a friend:

“I did not seek these (friendships) just for the sake of spending time with them and far less for the sake of simply forming connections; I sought (their company) for the quality of the people, intellectually estimated. Still all things considered, I feel best satisfied to forego the associations alluded to, for I was often compelled to countenance customs to which in reality I am averse.”

One can only presume he might be alluding to women and drink! But William Dick immediately realised his academic potential and straight away employed him first as a demonstrator and later as Assistant Professor of Anatomy and Physiology. John became a notable figure in the intellectual and literary society of Edinburgh, a group who were all strong Liberals in politics. A particularly close friend of his was another Edinburgh Quaker, Joseph Lister, who later reformed surgery with the use of antiseptics. John was soon elevated to the title of Professor and his short successful career in Edinburgh was summed up by his illustrious peers. Professor William Gardner who became Glasgow’s first Medical Officer of Health described John Barlow as a: ‘great and original thinker, so truthful and unselfish’.

Sir James Simpson the pioneer of chloroform wrote:

“He was a man destined to advance and elevate veterinary medicine’; while Professor Goodsir, wrote: ‘John Barlow was a man of very remarkable ability who helped establish a course every bit as eminent as the School of medicine.’

Mr Dun who taught Diatetics wrote:

“I never knew anyone whose influence on those with whom he came into contact was so wholly and powerfully good,” adding that “Professor Barlow’s scientific investigations and writings were well to the front of his profession. He was in all a man greatly beloved, nay revered by his students.”

William Williams in a speech made at the opening of a new college, declared that: ‘John Barlow was the pioneer of Veterinary science...a man living one hundred years before his time. Others were rule-of-thumb practitioners, while he brought the light of science to bear upon his profession.”

He was highly regarded and his published papers in the Veterinarian and as veterinarian correspondent for The North British Agriculturist, were widely read and still form the basis of modern research. He sadly died before his time, probably from Meningitis which spread to his spine and his last weeks of illness were extremely painful. He first began to be seriously ill on New Year’s Day 1856 when he was only 40, though initially it was thought that it was only rheumatic fever, and that he would recover. But it was in fact a very serious spinal infection and he soon became extremely sick and after a great deal of suffering, he died on January 29. But that is to pre-empt matters. John Barlow was an active member of the Edinburgh Meeting House in the Pleasance, where in 1851 he met Eliza Nicholson of Whitehaven whom he eventually married. Eliza it will be recalled, was the descendant of the family that possessed the Bible. It was a close knit circle as we have already seen, with Eliza’s sister Sarah marrying another Friend, John Wigham of Edinburgh and her sister Jane, marrying Jonathan Carr.

Professor

Barlow’s and Eliza’s home in Edinburgh

On New Year’s day, 1851 he and Eliza Nicholson were married and according to our Grandmother ‘entered one of the most perfect unions that earth affords.’ They moved into No 1 Pilrig Street, where their three children were born. This was and still is a fine Georgian house, built in 1805, the first in the street and from the outside, has a rather stern and formal exterior, somewhat reflecting the demeanour of its one time occupant. But it in no way prepares one for what awaits inside the house, now lovingly restored by the present occupant, John Campbell. For, to echo Howard Carter’s response to Lord Carnarvon’s famous remark ‘Can you see anything?’ at the entrance to the tomb of Tutankhamun, one can only say, with him, ‘Yes, wonderful things’. A hallway that opens on to the most splendid spiral staircase, which curves and winds its way up three floors to a fantastic oval cupola that lights up the whole central area of the house. From the spacious and elegant front dining room to the exquisite drawing room at the back, with its fine bronze fire place and tiled hearth, which still warms the room, itself given added grandeur by a dramatic curved end wall, with shuttered windows that overlook a beautiful long garden, is redolent of a more gracious age. Ascending the staircase one reaches a large master bedroom and several children’s rooms and at the very top, still sizeable maid’s quarters, while below the hallway is a huge basement where the old kitchen and storerooms would have been. There is still an air of tranquility about the house and sitting in the room where John Barlow died so painfully, I suddenly felt close to a person I had only previously read about.

Their three children were Alfred who died when he was only six (1851-7), Mary (1853-1899), and John Henry (1855– 1924). So Mary was only three and John Henry only four months when their father died and certainly JH would have had no memory of him. But according to both the pamphlet produced by Quakers when he died and by Granny Barlow’s account ‘he loved his dear children almost to idolatry’. To all who knew them, it was a very happy marriage and John ‘seemed the beau ideal of all that is noble and truly manly.’

John and Eliza remained in Edinburgh and he continued his work at the College where he had studied and was appointed Professor in 1855 introducing microscopical research and writing many treatises that were ground breaking in their time.6 He had been admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts in 1852 and also as a member of the Physiological Society. The standing he had among the scientific men with whom he mingled and worked and the appreciation of his talents and acquirements won in the Edinburgh Schools of Medicine was second to none. In 1856 he was engaged in compiling the first ever text-book of veterinary science when his last illness began and he died that same year.

As The Scotsman later stated:

“Nothing was ever more wanted than a good anatomical text-book for the veterinary student. The late lamented Mr Barlow had begun one but sudden death took away one of the best of anatomists, of teachers and of men and for a time, our hope of a text-book.”

His death was widely mourned both in Edinburgh and throughout the medical world. His achievements were perhaps best described by Professor Sir James Simpson, Professor of Anatomy in the University.

Writing in The North British Agriculturalist, he said:

“His character was indeed of a very high order both intellectually and morally. He was wonderfully informed on many of the most intricate modern questions in anatomical science. He was a man destined to advance and elevate veterinary medicine; and we all deplore his loss, the more so as he has been removed from among us while scarcely in his prime. ….People who knew him well respected him deeply, not less for his amiability and kindliness of heart, than for his great talents and high intellectual cast of mind.”

And another colleague, Dr Fleming wrote to Professor Barlow’s daughter Mary:

“I was a student under Professor Barlow from 1852 to 1855 and he had not long been married when I went to the college. My remembrances of him are particularly vivid; for his instruction,

manner and almost paternal kindness and interest in the students, made him greatly beloved, nay revered by them. He stood in the forefront of scientific men of his generation. In the veterinary profession of those days or even since, there has not, in my opinion, been his equal; and his all too premature removal from our midst was one of the heaviest misfortunes that has befallen our branch of medicine…..He won the hearts of all the students, never begrudging time or trouble in helping or looking after them…..A testament to his outstanding ability from my own experience when I was with the Army during the Crimean war. The fact remains that there have only ever been six principle veterinary surgeons since it was taught in colleges in this country and of these, three studied under your father which must be gratifying to your mother. To me he has always been an ideal image of goodness and perfection and in my own professional career I have always had it before me.”

When he died John left ample provision for his widow with shares in tin mines in Cornwall and the Glasgow Bank, but both of these were to crash.7 These were the days of unlimited liability and Eliza Barlow had to pay out again and again to creditors until she was left with only £200 a year with which to bring up and educate the children. In addition, as if this were not enough, not long after, their eldest son Alfred died. As the wife of a Professor and with the Nicholson money she would have brought with her, she had been used to a relatively easy and comfortable life with maids to look after them, but this financial debacle meant that they had to move to a smaller house in the city nearer to their cousins the Wighams in Salisbury Road who were very kind, especially ‘saintly Sarah Wigham’, who taught the Barlow children for a while. As with many Quaker families, they tended to look after each other and in accounts of John Henry and Mary’s childhood holidays, one often reads of them - Eliza’s sister Sarah and her husband, John Wigham - all going away together, often on sailing trips to Scotland. Granny Barlow writes in her memoir:

“Sometimes big parties of cousins were arranged, Barlows, Carrs, Wighams, Ashbys, Peiles with JHB acting as courier and financier....Mary, full of fun and very racy....and John, quieter but apt and quick in repartee.”

Eventually Eliza moved to Carlisle to be near her eldest sister Jane and her husband Jonathan Carr, where she and the two children lived in the upper part of a big old fashioned house above the baker’s shop that Carr had first opened on his arrival in the city, just opposite Carlisle Cathedral. It maybe that there was a certain amount of guilt involved here, as JD Carr, against good Quaker principal had indulged in a speculation in 1850, investing in a Cornish tin mine, encouraging others, including John and Eliza Barlow to do likewise.

As already stated the tin mine crashed and all who had backed, it lost their money. JD always felt he was responsible and resolved to reimburse other investors, selling the family home and using the money to recompense the other investors. Housing Eliza and her children was his way of helping to make amends.

For the rest of his life Jonathan Carr rented a house, Coledale Hall in Newtown, as though ‘doing penance for a piece of uncharacteristic vanity....protecting himself from delusions of grandeur’ as Margaret Forster puts it in her book on the Carr family.8

John Cambell, the present resident (left) and Antony R. Barlow on the steps of 1 Pilrig Street,

Edinburgh. Seen here 2014 Nov 17 before the erection of a blue plaque.

John Cambell, the present resident (left) and Antony R. Barlow on the steps of 1 Pilrig Street,

Edinburgh. Seen here 2014 Nov 17 before the erection of a blue plaque.

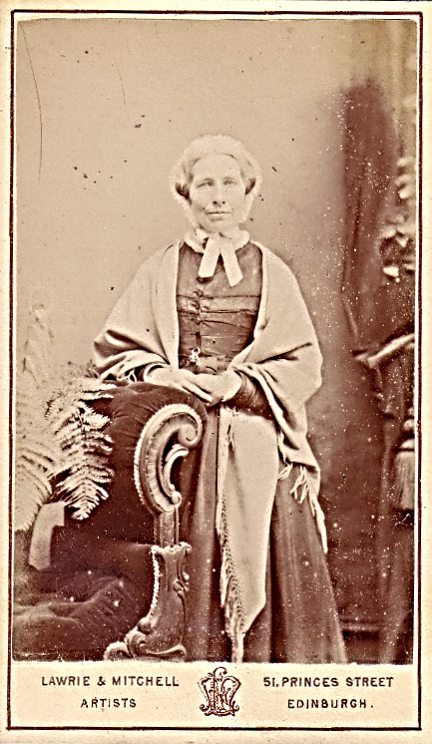

‘Saintly Sarah’ and John Barlow’s microscope

“Sarah Wigham, (née Nicholson) the sister of Eliza, (who married Professor Barlow) and Jane (who married Jonathan Carr), described as ‘saintly’ by our Grandmother, for the way she cared for the children.

As with close Quaker families of the period, when troubles befell a relative, they all rallied round and when Professor John died at the age of only 40 and Eliza was left with the children and declining finances, she and the children initially stayed with the Wighams at their Salisbury Road house, before moving to Carlisle to live with her other sister Jane in part of the Carr house.”

“John Barlow, was appointed Professor of Veterinary studies at the Royal Dick University in Edinburgh in 1855 and introduced microspical research. On his death our grandmother, Mabel Barlow donated his microscope to the college. Sadly, it appears to have been lost.”

1 In a note from a book on the Family Barlow privately published in 1911 it states: ‘The Oaks is known to have come into the possession of the family when it was sold by the Hough family to a John Barlow, who died in 1658. The greater part of the property was sold after the death in 1846, of (the then) Sir John Emmott Barlow. A small portion still remains in the family.’ It was pulled down in the 1875 to make way for the railway line.

2 John’s brother Thomas born in 1825 married Mary Ann Emmott and their son John Emmott Barlow married the Hon Anna Denman who I remember visiting in her London flat in Grosvenor House when I was about nine or ten. John Emmott was made a baronet in 1907 and became MP for Frome in Somerset. The present holder of the title is his grandson John Kemp Barlow of Bradwall Hall.

3 Deborah Neild was a cousin of John Camden Neild, an eccentric, who left his fortune to Queen Victoria – see Chapter 12

4 Carol Saker’s archives

5 The anatomy, especially the comparative anatomy, of animals.

6 When John Henry died my Uncle John and my Grandmother offered his microscope to the Royal Dick in Edinburgh in 1929. For more see page 9

7 See under J D Carr p 42

8 ‘Rich Desserts and Captains Thin’ (Chatto and Windus).